The Dirty Little Secret About Failing Fast

Failing can be less a function of the market and more about human nature.

Have you ever heard of the Yerkes-Dodson Law? Neither have I.

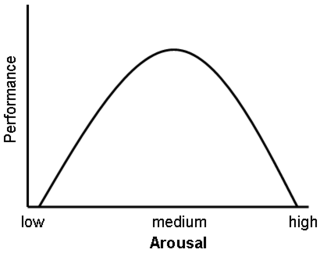

However, in today’s performance-driven world, it might be one of the most important laws of innovation and productivity. The Yerkes-Dodson Law states that there is a relationship between performance and arousal. In other words, an increase arousal can help improve performance—but only up to a certain point. Now here is a key point: at some level of arousal—when it becomes excessive—performance will diminish.

Source: Wikimedia

The paper was published in 1908 where rats were given mild electric shocks to motivate them to navigate a maze in an attempt to optimize performance. As illustrated in the graphic, performance clearly had a zone where added arousal improved performance. However, it also resulted in a “performance inflection point” where gains were decreased. Of course, the extrapolation from rats to humans may be a stretch. But conceptually, the application of this principle in the maze-like world of business and innovation can apply.

Failure can belong to the market and the employee.

In theory, there appears to be a threshold or inflection point where small changes in arousal can result in dramatic changes in performance and it happens fast. And that leads us to today’s tactic to drive growth and innovation: fail fast.

So, failing by design allows us to “market test” an idea and respond directly to the voice of the marketplace. But the Yerkes-Dodson Law informs us that failure can also come from internal forces and pressures to drive success. So, the push to fail might really reflect an internal failure as employees are shifted to the right on the curve and performance declines.

Has Elon Musk reached his Yerkes-Dodson tipping point?

Innovation rock star Elon Musk has been recently sited as pushing himself to the point of exhaustion. And in this context, Musk has been blamed for hurting Tesla with his bizarre behavior. It seems that Musk might be driving himself over the top of the performance curve, finding himself driven, but with less functional capacity to achieve his lofty goals. Performance—of Musk and of Tesla—can be directly impacted even with the best technology and planning. The problem is a very human one.

Innovation and the pressure to perform.

As businesses ride the exponential curve of innovation, avoiding the risk of obsolescence is one of leaderships’ top concerns. And that concern can fuel the pressure for individual performance. The construct of failing fast is generally considered a test of market viability. But the failure may also be due to human causes. The pressure to perform can push people to the point where viable ideas and technologies are compromised. The process of innovation (and the tactic of fail fast) must take into consideration where people are on the Yerkes-Dodson curve and how motivation and arousal can directly impact performance. Striking the balance between motivation and capabilities is essential. After all, driving innovation and performance might just be a bit like the Goldilocks principle—not too hot, not too cold, but just right.